New Study: Assessing Welfare Levels in Early Life Stages of Indian Major Carps

- Haven King-Nobles

- Jul 3, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 1, 2025

Summary

FWI has so far primarily focused on improving welfare of Indian major carps at the final stage of the farm cycle—the “grow-out” phase. Yet this is just one part of the fishes’ lives, and there are compelling reasons to believe that a greater impact is possible in the earlier stages. For instance, one farm can hold millions of fry, and mortality rates can be extremely high, seemingly even around 50%.

This post introduces our newest study, launching this month, which aims to identify cost-effective interventions to help fishes at these earlier life stages.

Context: Indian Major Carp Life Stages

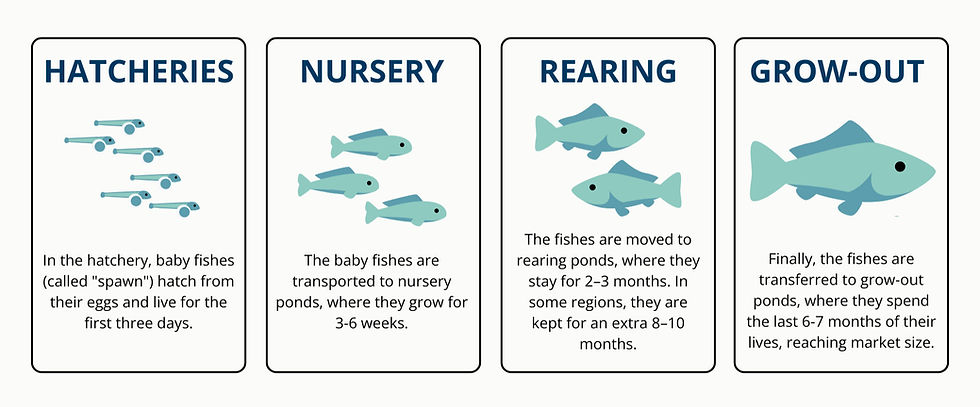

In any species of farmed fish, the most visible farms are generally only the final life stage (the grow-out stage). Throughout the lives of these animals, they are generally transported 2-5 times to different stages as they grow, to maximize the efficiency of farming them. For instance, in the case of Indian major carps—our primary target species—their life cycle on the farm generally1 consists of the following stages:

Hatchery: This is where the baby fishes hatch from their eggs and live for about the first three days of their lives. The parent fishes (“broodstock”) will live here for years, and are bred several times a year. Baby fishes in a hatchery are called “spawn”.

Nursery: After the hatchery, the ~3-day-old fishes will be transported in bags to a nursery pond. These ponds are generally 500–1000 m² in area, with each holding several hundred thousand “fry” or more. Here, the fishes grow for 3–6 weeks, transforming from tiny larvae into fry about 2–2.5 cm long.

Rearing: The fishes are then moved to rearing ponds, which are generally larger—about 2 to 10 acres. Under standard conditions, fry stay here for about 2–3 months, growing into fingerlings roughly 10–15 cm long (around 10–20 g). However, in coastal Andhra, many farmers deliberately keep these fingerlings at high densities and feed them minimally for an extra 8–10 months, producing stunted “yearlings” that reach 200–250 g. Yearlings are preferred because they handle transport and low-oxygen conditions better and often show rapid “catch-up” growth once stocked in grow-out ponds.

Grow-out: Finally, fishes will be transported to grow-out ponds, where they will live the last 6–7 months of their lives. This stage has been the primary focus of our farm program, with grow-out farms comprising about 65% of current active farms (most of the rest being rearing/grow-out farms).

In this study, we have chosen to focus on fishes in the nursery stage, primarily for the following reasons:

Hatcheries seem generally more secretive and less accessible.

Fishes are still very concentrated in the nursery stage, whereas they are less concentrated in the rearing and growout stages.

Poor conditions in earlier life stages seem to be an issue more broadly for aquaculture. For instance, we are aware of this study in Norway, which found high mortality rates in Atlantic salmon hatcheries, and we have also heard of this issue occurring in other contexts.

It’s worth noting that, as a r-selecting group of animals, fishes naturally have high mortality rates in their young, at least to our human eye. The real question for us as fish advocates is how much of this mortality is inevitable, and how much reflects poor welfare on the farm.

The Problem

Based on our initial report on earlier life stages, and based on our later conversations with farmers, conditions in nurseries may cause poor welfare for the animals who live there. We were specifically concerned to learn from multiple farmers that some nurseries have mortality rates at about 50%, which we expect to be indicative of suboptimal environmental conditions (e.g., excessive stocking densities).

The upshot of high mortality rates is that farmers have some economic incentive to reduce them. We intend for any intervention we develop here to, in part, be incentivized by farmers taking an interest in lowering their nursery mortality rates.

The Study

To better understand conditions in nurseries so that we might later develop interventions for them, we are planning a 6-month investigative study. This study has the following stated objectives:

Identify nursery practices negatively impacting fish welfare.

Discover existing or potential interventions to address these issues.

Understand barriers to adopting improved welfare practices.

The study will occur in two phases, with us only proceeding to the second provided that we are satisfied with the outcomes of the first:

Phase 1: Interviews and Initial Observations (15–20 nurseries)

Phase 1 will begin this month and will involve semi-structured interviews and preliminary observations with 15 to 20 farms in order to identify the practices that separate better nurseries from the others. Of particular focus will be feed quality, spawn transportation, water quality management, handling practices, and biosecurity measures.

Midpoint Review and Prioritization

During this review, we will assess whether we have found useful, welfare-indicative distinctions between the nurseries. If so, we will proceed to Phase 2; otherwise, we will end the study here.

Phase 2: Detailed Observational Study (8 nurseries)

This phase will involve more in-depth observations at 8 farms, selected from the 15 to 20 farms visited in Phase 1.

This study will be led by FWI’s Project Manager, Teja Sangeetha.

Next Steps

As usual, we will keep our blog updated with our results. Our hope here is to identify a cost-effective intervention that we can scale across nurseries in India, and that also may inform the work of our fellow advocates around the world.

For more information, you can access our internal docs on this study.

1Note that we are oversimplifying a little, as these stages often blur together and other stages are slight variants of what we have listed here (e.g. the “breedout” stage). For these reasons, it is also difficult to obtain precise definitions here.

Comments